|

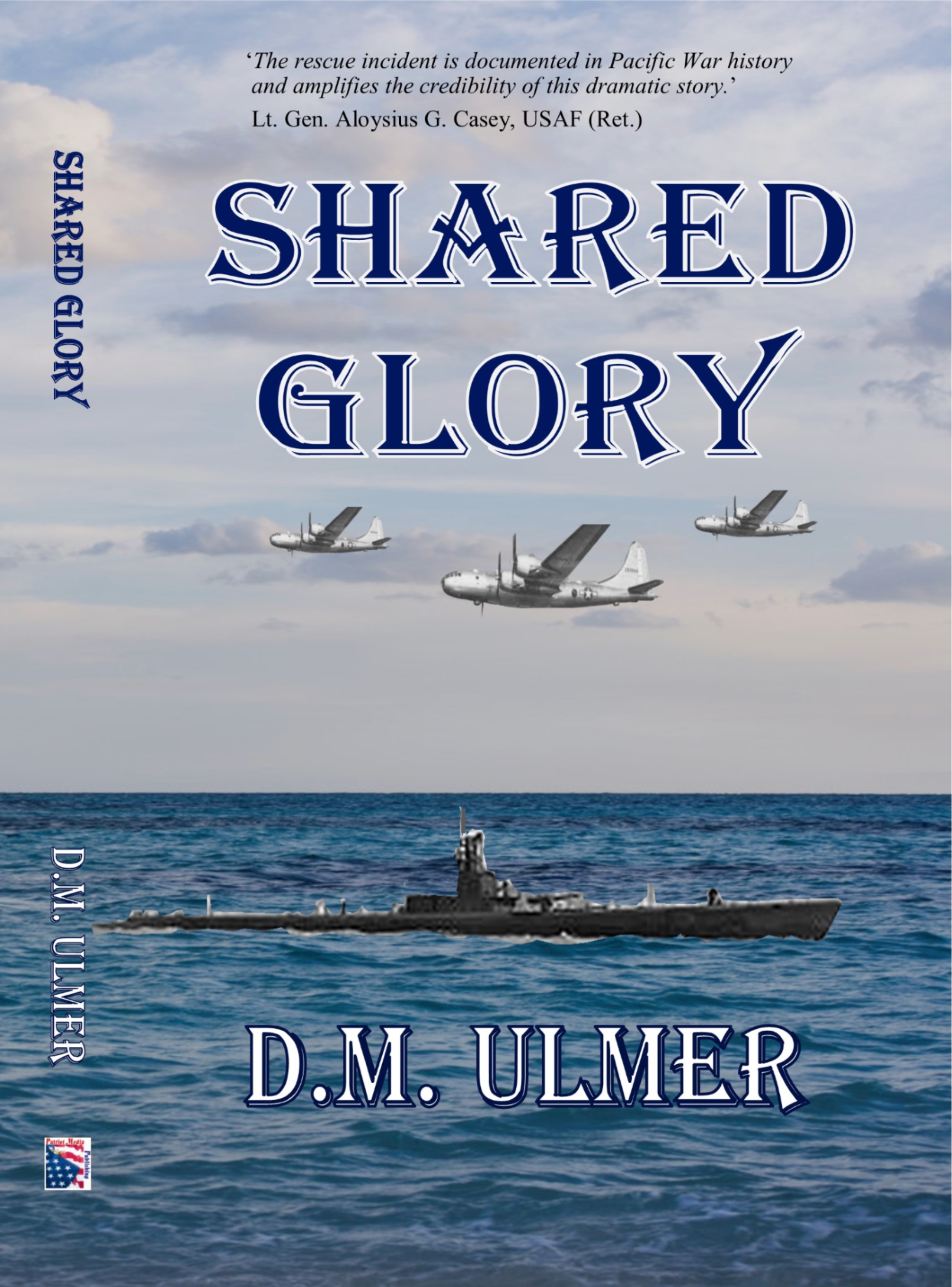

Shared Glory

Modern literature includes many coming of age stories, but few are as exciting as those that describe the process as it took place in the caldron of WWII. Then, young men and women had to not only contend with the drastic changes enforced by maturity, but they also faced radical changes in the role of men and women in western society as the massive effort to counter the Axis powers affected every phase of their lives and that of their families. As young men departed the protective cocoon of home and school they were forced into the regimentation of a military indoctrination that could not cater to personal comfort or whims; it was theirs to learn how to follow or lead as talent and background prepared them to accept the challenge. All the norms of easing into work and family responsibilities with the aid of parents, siblings, friends and mentors were gone as the military forged one more combat fighter. It was equally upsetting for young women to sort out developing relationships when virtually all the males they knew were either in service or on their way to donning a uniform. They accepted new roles in family structure and the larger society without a fixed roadmap. They learned to deal with separations, working in formerly male environments, and writing morale building letters. The long depression from which all were emerging had forced its own dreary regularity, but then it became an entirely new world. Don Ulmer captures the essence of these changes by his careful character development and simply telling their story as it unfolds. He is at his best however, covering the high drama of combat operations. The complexity of war machines, the rigors of training and the startling suddenness of enemy attacks highlight the indelible changes to the lives of the men who fought World War II. He brings the reader up close to the action where fear, heroism, and at times tragic loss seize the moment. A brilliant submarine skipper balances the risks to his own crew as he operates on the surface in enemy waters to save a downed B-29 crew. Ulmer’s own experience as a veteran submarine officer allows him to vividly portray the decisions required to fight the deadly battles that allowed the allies to prevail. The rescue incident is documented in Pacific War history and amplifies the credibility of this dramatic story.

―Aloysius G. Casey Lt. Gen., USAF (Ret.) Frontlines of Freedom Interview Submarine Novels by D. M. Ulmer - Reviews

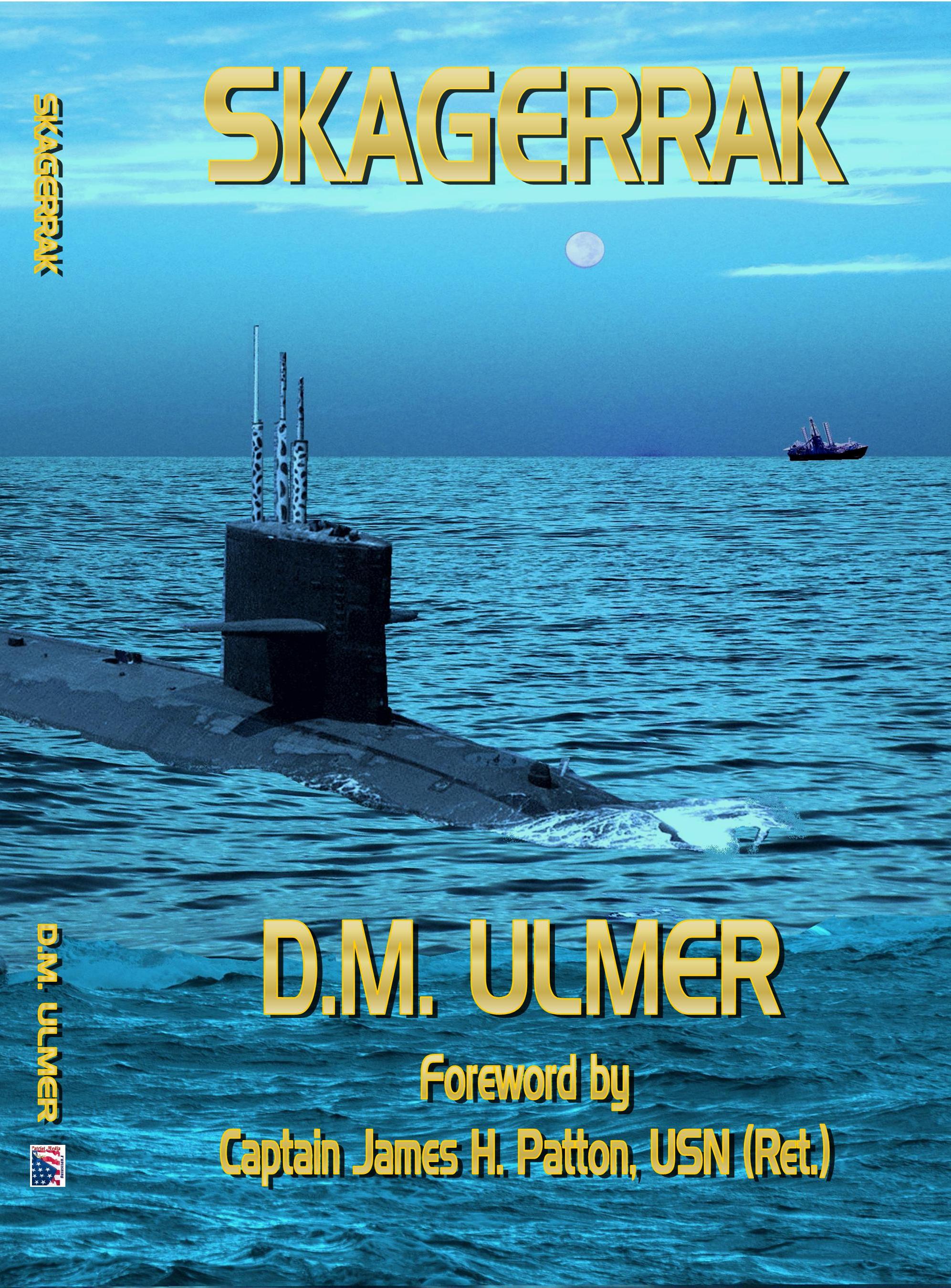

Skagerrak Review: 'I've read all of D.M. Ulmer's books and enjoyed each one. I found Skagerrak to be one of his best; exciting suspenseful and historically accurate. It captures challenges confronting the Cold War US Submarine Force, plus those of the Soviet Warfare Navy. Ulmer researches locations and cultures well; some of his insight into Scottish customs and fascinating use of language may be attributed to his personal experience. I recommend Skagerrak. It is an exciting read with keen insight into submariner life and the many personal stories covered.' W. Michael Richardson

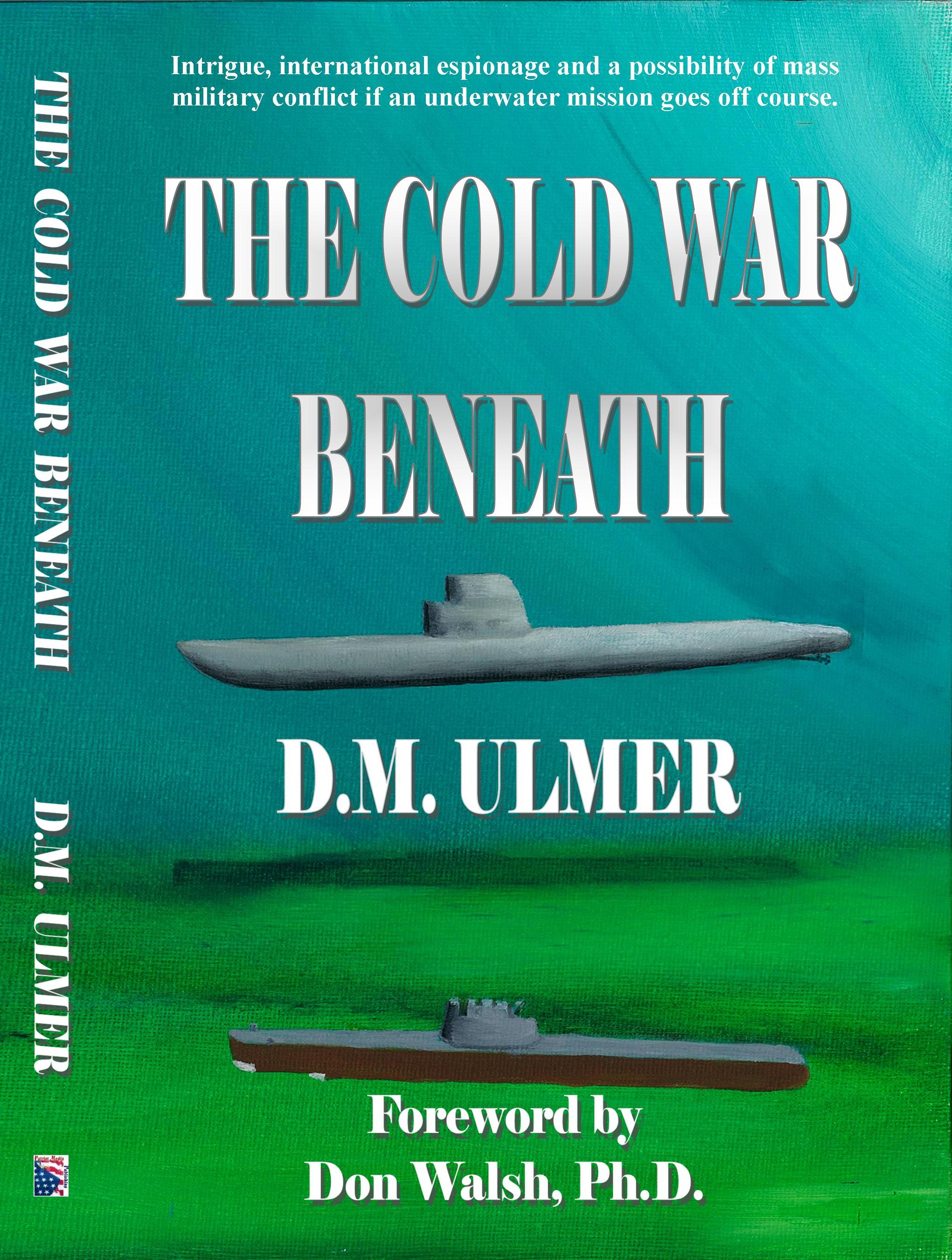

Review: The Cold War Beneath, by Dr. Don Walsh, USN

(Ret.)

This book is a work of fiction. But authoritative, well-written submarine fiction can be both entertaining and informative. This is especially true in the case of highly classified Cold War submarine operations; details still remain locked away. Secrecy oaths and strict ‘need to know’ policies continue to guard the nature and results of those operations. The truth may remain untold for some time into the future. Fiction written by participants in those operations can be useful to give us an insight into those tense years of undersea conflict. It is said that submarines are the ultimate stealth platform. Long before specially configured ‘low signature’ aircraft were called “stealth”, the modern submarine had proved itself to be the optimum means to covertly look into the competition’s ‘backyard.’ This permitted the collection of valuable intelligence with little chance of being detected. Both the United States and the Soviets actively used submarine platforms to track and observe the other side. Patrols off each other’s coastlines, observing military operations and collecting electronic signal intelligence, were all part of the game. In this novel, Captain UImer provides an idea of how such operations were conducted by each side. To ‘set the scene’ for this book, it is useful to consider U.S. and Soviet submarine development during the four and a half decades of the Cold War (1947-1991). The USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) had an inherent numerical advantage but one not realized in practice. Historically, their navy was a coastal defense force. When WWII began they had 218 submarines, the world’s largest submarine fleet. However, almost all of it was smaller coastal ships with limited capabilities. Most of their operations were in the Baltic, Black Sea and to a lesser extent, the Far East. It was not a ‘blue water’ force. After the war, the allied and Soviet military forces eagerly sought a wide variety of weapons used by the Germans and Japanese. Here was an opportunity to ‘shop’ for new technologies that could be adapted to the armed forces of the victors. The United States and the USSR were particularly aggressive collectors. There was a special interest in the latest German U boats some of which were far more advanced than anything the allied navies had. Especially important was the Type XXI, the last major class of German submarines. It could dive to 440 feet and had a maximum submerged speed of 18 knots. A snorkel system permitted operation of the engines while submerged giving them greatly increased underwater endurance. Huge batteries provided longer submerged operations at higher speeds. Careful attention to hull streamlining greatly reduced submerged drag. By comparison, the more angular WWII USN fleet boat could dive just about as deep but had a maximum submerged speed of only 8 knots. Smaller batteries meant they would have to be recharged daily on the surface. The USSR intended to replace their submarine force that had been greatly diminished during the war. They got four of the latest Type XXI submarines as war prizes plus some shipyards that built them. That captured know-how was the basis for construction of a new fleet. The result was an astounding build of 215 submarines of the NATO “Whiskey Class.” By the mid-1950s, the Russian diesel submarine force was the world’s largest and its numbers would increase during the Cold War years. For example in 1979 the Russians had 370 submarines (including nuclear boats). By comparison, the U.S. Navy had only 116 that year. At the end of WWII the United States’ situation was different. While they had gotten two of the new Type XXI boats, the Navy had in service 150 relatively new “fleet boat” submarines. Experts believed that these were the finest long-range patrol submarines in the world. So the Navy’s approach was to selectively use captured German technologies and adapt them to conversions of the fleet boats. This was the basis for the GUPPY (Greater Underwater Propulsive Power) program. The fictional USS Piratefish in this novel depicts one of these. A snorkel mast was added; hulls and conning towers were streamlined to reduce hydrodynamic drag and the size of the storage batteries was greatly increased to provide much greater submerged endurance. As a result, the best of the GUPPY conversions could go slightly faster submerged than on the surface. And they could remain submerged for long periods of time using their snorkeling capabilities. Indeed it was not uncommon to remain submerged for over two months during special intelligence operations. Also German submarine designers gave special attention to sound silencing. These ideas were also incorporated into the 52 converted fleet boats. The result was a highly capable and very quiet reborn fleet boat. Various types of GUPPYs would continue to serve in the Submarine Force up until the mid-1970s. In addition to improved submarines, both navies worked to add missiles to their on board capabilities. The first steps were air-breathing missiles adapted from German designs. The well-known V-1 pulsejet, essentially an unmanned airplane, was tested on board Soviet and U.S. Navy diesel submarines in the late ’40s. By the end of the ’50s, cruise missile capabilities were becoming operational in both navies. The U.S. Navy’s Regulus I cruise missile fitted with a nuclear warhead was on board submarines off the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East from 1959-1964. The major weakness of these weapons is that they required the launch submarine to remain surfaced for a significant period while the missile was set up and launched. This greatly compromised the stealth property of these submarines. Ultimately the USSR developed and perfected cruise missile systems. Both navies would eventually put these air-breathing cruise missiles on board nuclear submarines. While this gave the platform longer range and mission duration, they still had to surface to launch weapons. Nevertheless, the Soviet Navy eventually had 50 cruise missile submarines in service. This was driven by a primary mission to counter U.S. Navy aircraft carrier groups. The ‘holy grail’ was to develop a means to launch missiles while the submarine was submerged. The Russians did it first with an experimental submarine launch in 1956. But in 1960 it was the U.S. Navy’s Polaris Program that put the world’s first submarine launched ballistic missiles into operational service. The Soviets soon followed and their deterrent patrols became a Cold War fact of life. In the mid Cold War years both navies worked on the development of a wide variety of submarine designs and technologies. And both navies were operating their submarines worldwide. For the USSR, their submarine fleet was no longer a coastal defense force. Its ballistic missile boats patrolled off our coasts and their cruise missile submarines tracked our aircraft carrier task forces. Both sides wanted to know what the other was doing. The submarine was the perfect stealth platform to find out. In the late 1940s, the U.S. Navy began highly classified patrol programs, “special operations”, that operated off the coastlines of the Soviet Union. They also trailed their submarines in the open ocean. We would covertly watch fleet and submarine operations, learning about their technologies, operational procedures and tactics. In addition, “spec ops” would employ electronic listening techniques to listen to their communications and measure the basic parameters of their electronic systems. Special teams of intelligence specialists, the “spooks”, would be on board to direct intelligence collection activities. Typically, diesel boats would go on patrol for about two months remaining submerged the entire time. They would run silently during the day while collecting ‘intel’ then snorkel at night to recharge their batteries. It was extremely difficult ‘submarining’ but an enormous amount of nationally important information came from those patrols. The advent of nuclear submarines made these missions easier, safer and more productive. The Russians were doing the same thing but not as successfully as the U.S. Navy’s operations. Their submarines tended to be noisy and easily detected. In addition, the way they manned, maintained and trained their submarine force was not as effective as with our submarine force. A lot of books have been written about diesel submarine operations in the post WWII era. Some are outright fiction while others claim to give the ‘inside story’. The fact is that most details of codeword submarine operations remain highly classified even though it has been decades since most of them took place. Many of the ‘inside story’ authors have had only limited experience with these operations. This has resulted in a high degree of conjecture most of it inaccurate. Submarines involved in spec ops only had a few officers and crew who knew the details and results of the patrol’s mission. Most of the officers and crew on board could only guess at what was going on. It was need to know, even in the small world of a single submarine crew. Captain Don Ulmer USN is in a unique position in this field of seagoing literature. A career submarine officer, he has participated in special operations in diesel submarines including having command of one. Furthermore, he later served in the nuclear powered Fleet Ballistic Missile submarines (FBM). While he is still bound by his security clearances, he can accurately write fiction that might or might not be a synthesis of his experiences during the Cold War. Don is an Annapolis classmate of mine and we were in the Submarine Force at the same time. I spent years in submarine operations before I got command, so I have a pretty good idea of accurate writing as well as ‘off course’ fiction. Don’s got it right in this book. This is his third in what will be a quintet about the U.S. Navy’s submarine service and how it fought the Cold War—events that happened even as the Navy made the dramatic transition from diesel to nuclear power. Captain Ulmer having served in both types of submarines is qualified to provide an accurate accounting of those times. As a talented writer he has brought to life a part of the U.S. Navy that is largely unknown. Few outside our organization knew what our real peacetime mission was. That was fine for those of us in the “Silent Service”. The surface Navy and other armed forces thought the Navy’s submarines just did a lot of training as well as providing target services to ships and aircraft. Even our families did not have a clue as they had no “need to know”. All they knew is that from time to time we would be out of communication for two months or longer. When we got home, we could not talk to anyone about what we had been doing. Sure, it would have been great to brag about a particularly successful patrol but our secrecy oaths prevented that. So it is not without reason that we called ourselves the “Silent Service”. Stealth weapons do not like to be seen or known. Your life depended on being and remaining unknown…

James H. Patton, CAPT USN (Ret) and technical

advisor to the film Hunt for Red October states in his review, 'Captain Ulmer parlays his knowledge and

experience gained from command of a US Navy Diesel-Electric submarine and earlier service as a Department Head on one of the

first nuclear-powered Polaris ballistic missile submarines to craft a fascinating 'alternative history' in the early

part of the last decade of the 20th century … unusual in this “techno-thriller” genre, Silent

Battleground absolutely reeks of both technical and tactical credibility … readers will find a delightful blend of

elements from On the Beach, Incredible Victory, Thirteen Days and Hunt for Red October. Submariners

will approve, non-submariners will learn, but all will enjoy Silent Battleground.'

The late Donald S. Campbell Jr., CAPT USN (Ret) , who once worked in the Office of Submarine Warfare (OP-31) in the Pentagon, wrote: 'Captain Ulmer's conjecture framed in his novel Silent Battleground envisions a realistic possibility of internal confrontations within the US submarine officer corps had the Cold War turned hot in 1987. In this regard, he provides interesting insight to a professional issue kept submerged within the Silent Service community. Did the technical broom of nuclear propulsion sweep away a nucleus of officers, highly qualified and needed to insure combat readiness of the Submarine Force? A revealing read for submariners and lay persons alike.' JR Reynolds, author, Sustenance of Courage and Woman of Courage 'Silent Battleground is a powerful, compelling novel. Author, D. M. Ulmer, a Navyman of 32 years, moves the reader through tense events with skill and expertise using his professional savvy to lace the plot with intrigue and speculation that makes the book a page-turner. Ulmer's rare talent exposes torn loyalty and self discovery the characters endure. They serve with duty, fear, and vengeance but the human element of love and family challenges them. I found myself believing fiction to be fact possible. Dave Bartholomew, CAPT USN (Ret) and former commander of two US warships writes: 'Don Ulmer’s Silent Battleground leaves me breathless at the end of every chapter. Don brings us, realistically, into the shipboard world. His wardroom scenes are so realistic that I found myself there. Don shows us a scenario that very nearly happened. In doing so, he not only gives us a view of professional Navy officers, but opens a rare glimpse into the war-fighters’ personal lives – on both sides of a conflict we hope never happens.' Robert J. Neal, author of Smith & Wesson 1857-1945

reviews Silent Battleground by D.M. Ulmer

Book Review: It was suggested by a

friend that I might find "Silent Battleground" by D. M. Ulmer a good read. I took the suggestion and ordered the

book. It arrived and that evening after dinner I started on it. I got half way through the book at about 10:30 that night

and decided I had better get to bed. It was a tough decision I will have to say. After breakfast the next day I picked it

up again - just couldn't wait. I put it down - finished at 2:30 that afternoon. I found the book spellbinding. Ulmer certainly

knows how to spin an excellent story line. He is an expert in the subject about which he is writing and I appreciated his

abilities to bring both reality and human nature into the story. I am perhaps unique in this particular case. I am an engineer,

so I like his excellent presentation of the technical aspects of the submarine. I am also a published author (four books and

50 magazine articles) so I know writing ability when I see it. I live in Washington State very close to the area around which

he based his book. I have been to every place he mentions, they really exist and he accurately describes them and their military

functions. Last, but not least, I am a romantic as well, and the rule for me is that the guy and gal must get together in

the end of any story. They do. Robert J. Neal

REVIEW of Shadows

of Heroes |